On the Anielewicz–Hoffman groupoid spectrum

«After all, the truth – is a self-portrait»

J.Kaczmarski, "Kramsztyk’s crayon"1

I left the bike2 by the sky-carousel at the square3

A difficult journey in fountains of black smoke

The dizziness and sensation of fainting became very strong2

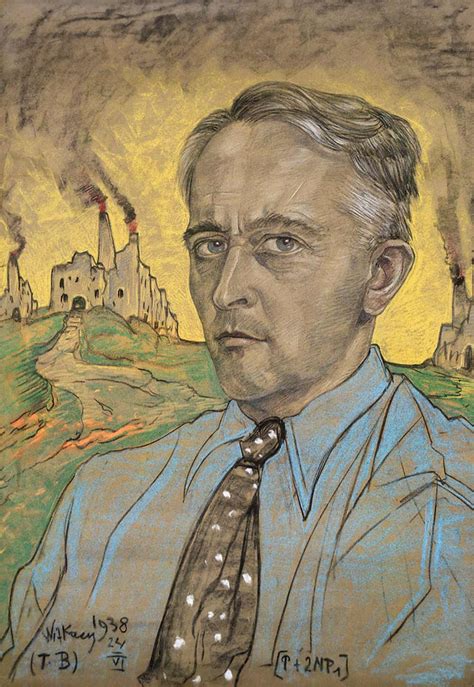

Smokestacks which burn in the background of the 24 VI 1938 self-portrait4a suggest

That solving the problem of excessive colorfulness of the world of living

Was a sufficient condition for the revelation of dead rainbow’s hosanna

On a clear spring evening3

Let us share the hermetic5 host of alienation4b

Covered with the sketches of the last days behind the wall1

Let the mirage of gnosis be bitter in taste

Let it stick in our throats like a burnt fruit

From the book left to us in ashes

(19.IV.20/19.IV.21, 仁座町/ווארשעווער געטא;

transl. from Polish by Michał Kotowski, 19.IV.21, Warszawa)

Footnotes:

1 – «It is hard to be surprised by the irritation

Of us, who were rushed to removing traces

Of the final solution of Judenfrage.

We poured out inert bodies,

Stripped of the remnants of identity, – under duress. (...)

On black and white document plates

One can see our dehumanised faces.

Only the SS-man, playing with a severed head,

Reveals his human face.

His smile expresses free will

Of a being at the highest stage of development.

It is impossible to not be afraid of him – he is alive and beautiful

And unappealably triumphant.

Who would dare to set limits

To his imagination and outright violence?»

2 – «4/19/43 16:20: 0.5 cc of 1/2 promil aqueous solution of diethylamide tartrate orally = 0.25 mg tartrate. Taken diluted with about 10 cc water. Tasteless.

17:00: Beginning dizziness, feeling of anxiety, visual distortions, symptoms of paralysis, desire to laugh.

(...)

I had to struggle to speak intelligibly. I asked my laboratory assistant, who was informed of the self-experiment, to escort me home. We went by bicycle, no automobile being available because of wartime restrictions on their use. On the way home, my condition began to assume threatening forms. Everything in my field of vision wavered and was distorted as if seen in a curved mirror. I also had the sensation of being unable to move from the spot. (...) The dizziness and sensation of fainting became so strong at times that I could no longer hold myself erect, and had to lie down on a sofa. My surroundings had now transformed themselves in more terrifying ways. Everything in the room spun around, and the familiar objects and pieces of furniture assumed grotesque, threatening forms. They were in continuous motion, animated, as if driven by an inner restlessness. (...) Even worse than these demonic transformations of the outer world, were the alterations that I perceived in myself, in my inner being. Every exertion of my will, every attempt to put an end to the disintegration of the outer world and the dissolution of my ego, seemed to be wasted effort. A demon had invaded me, had taken possession of my body, mind, and soul. I jumped up and screamed, trying to free myself from him, but then sank down again and lay helpless on the sofa. The substance, with which I had wanted to experiment, had vanquished me. It was the demon that scornfully triumphed over my will. I was seised by the dreadful fear of going insane. I was taken to another world, another place, another time. My body seemed to be without sensation, lifeless, strange. Was I dying? Was this the transition? (...) Slowly I came back from a weird, unfamiliar world to reassuring everyday reality. The horror softened and gave way to a feeling of good fortune and gratitude, the more normal perceptions and thoughts returned, and I became more confident that the danger of insanity was conclusively past. Now, little by little I could begin to enjoy the unprecedented colors and plays of shapes that persisted behind my closed eyes. Kaleidoscopic, fantastic images surged in on me, alternating, variegated, opening and then closing themselves in circles and spirals, exploding in colored fountains, rearranging and hybridizing themselves in constant flux. (...) Exhausted, I then slept, to awake next morning refreshed, with a clear head, though still somewhat tired physically. A sensation of well-being and renewed life flowed through me. Breakfast tasted delicious and gave me extraordinary pleasure. When I later walked out into the garden, in which the sun shone now after a spring rain, everything glistened and sparkled in a fresh light. The world was as if newly created. All my senses vibrated in a condition of highest sensitivity, which persisted for the entire day.»

3 – «In Rome on the Campo di Fiori

baskets of olives and lemons,

cobbles spattered with wine

and the wreckage of flowers.

Vendors cover the trestles

with rose-pink fish;

armfuls of dark grapes

heaped on peach-down.

On this same square

they burned Giordano Bruno.

Henchmen kindled the pyre

close-pressed by the mob.

Before the flames had died

the taverns were full again,

baskets of olives and lemons

again on the vendors’ shoulders.

I thought of the Campo di Fiori

in Warsaw by the sky-carousel

one clear spring evening

to the strains of a carnival tune.

The bright melody drowned

the salvos from the ghetto wall,

and couples were flying

high in the cloudless sky.

At times wind from the burning

would drift dark kites along

and riders on the carousel

caught petals in mid-air.

That same hot wind

blew open the skirts of the girls

and the crowds were laughing

on that beautiful Warsaw Sunday.»

4a – Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, 24 VI 1938 (self-portrait):

4b – «When everyone had gone home, Eliza gave him ten pills of Davamesque B2 — the same pills he had been given that time on the street — from her rather ample supply. (...) He awoke at two in the morning with a weird sensation. (...) A dark, thick curtain seemed to flutter before his eyes. He was mortified that he had lost his vision. He gazed over at the windows, which even on the darkest night shone red. Nothing — darkness, absolute and restless. Something writhed, much as if the ponderous bodies of terrifying reptiles had locked in battle in the impenetrable penumbra. At the same time he was visited by an absolute calm — the calm was normal, apparently. He lay scarcely conscious of who he was; he had transcended himself, was peering down into himself as though into mysterious caverns where something unknown was being fashioned. Till suddenly the billowing curtain exploded and he was showered with brilliant sparks. From the sparks strange and recondite objects began to form and to compete with one another: weird combinations of machines and insects, avatars of objective nonsense in greyish brown, yellow, and violet, embodied in a queer matter and constructed with a hellish precision. Suddenly the shower stopped, and Zip realized that this was a three-dimensional curtain of a higher order, concealing another world in another space. A distinct and three-dimensional image, but where, in what continuum? And later, though able to summon the images, he could never fully reconstruct this remarkable impression in all its immediacy and freshness, being left with only comparisons: its essence eluded man’s normal senses and spatial sense generally. (...) Zip felt an inner refulgence; he was a beam speeding through the infinite void toward a crystalline creature (not really a creature; hell only knew what) iridescent with unknown colors, which turned out to be the eternally untrappable Maximal Duo-Unity. The vision vanished; again confusion, the same diabolical curtain of invisible, writhing reptiles. And he saw his entire life, but as though engulfed in flame: deficient, riddled with gaps of appalling darkness in which some mysterious fellow (the same as before, only wearing Murti Bing’s expression) was performing amazing feats, now expanding to nearly unlimited proportions, now shrinking to something imperceptible and microscopically small, that something being the world’s very intestines — which was, in fact, a pile of improbable guts heaving in an erotic trance: the agitation of impersonal sex organs. This was his life, but now viewed with a critical eye from the vantage point of a higher — that is, not-of-the-human — purpose: its aims lay beyond this world (in that mysterious spatial realm?), but this life still had to be measured by them, otherwise the world’s potential would be diminished, even reduced to zero, in which case (O, horrors!) not only would a Non-Spatial Nothingness exist — something inconceivable — but also everything that had already been would be canceled out, and this would imply that nothing had ever existed or ever could exist. The prospect of this vacancy inspired incalculable horror. Hence that zealous obedience shown by the followers of Murti Bing. Self-annulment, cancellation of the past? How was that possible? Yet under the influence of Davamesque B2 such things were grasped as readily as the theory of functions.»

5 – «What were the emotional sources of the new attitude? They lie, it may be suggested, in the religious excitement caused by the rediscovery of the Hermetica, and their attendant Magia; in the overwhelming emotions aroused by Cabala and its magico-religious techniques. It is magic as an aid to gnosis which begins to turn the will in the new direction.

And even the impulse towards the breaking down of the old cosmology with heliocentricity may have as the emotional impulse towards the new vision of the sun the Hermetic impulse towards the world, interpreted first as magic by Ficino, emerging science in Copernicus, reverting to gnostic religiosity in Bruno. As we shall see later, Bruno’s further leap out from his Copernicanism into an infinite universe peopled with innumerable worlds certainly had behind it, as its emotional driving power, the Hermetic impulse. Thus “Hermes Trismegistus” and the Neoplatonism and Cabalism associated with him, may have played during his period of glorious ascendance over the mind of western man a strangely important rôle in the shaping of human destiny.

(...) the godless universe of Lucretius, in which that pessimistic man took refuge from the terrors of religion, is transformed by Bruno into a vast extension of Hermetic gnosis, a new revelation of God as magician, informing innumerable worlds with magical animation, a vision to receive which that great miracle, the Magus man, must expand himself to an infinite extent so that he may reflect it within.

(...) Drained of its animism, with the laws of inertia and gravity substituted for the psychic life of nature as the principle of movement, understood objectively instead of subjectively, Bruno’s universe would turn into something like the mechanical universe of Isaac Newton, marvellously moving forever under its own laws placed in it by a God who is not a magician but a mechanic and a mathematician. The very fact that Bruno’s Hermetic and magical world has been mistaken for so long as the world of an advanced thinker, heralding the new cosmology which was to be the outcome of the scientific revolution, is in itself proof of the contention that “Hermes Trismegistus” played some part in preparing for that revolution.»